Sometimes, when we interact with people we disagree with, it can feel impossible to have anything in common.

What if we’re not looking hard enough? What would happen if we took the time to listen to each other, understand where people are coming from, and try to understand their feelings?

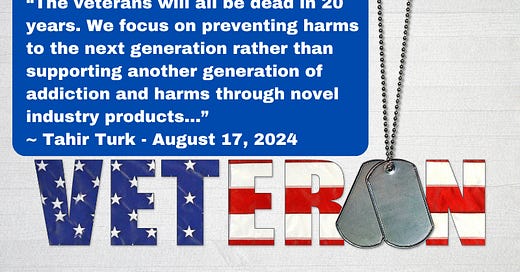

The quote in the graphic above is a comment made on one of my tweets. My reaction to it was anger. I felt it was cold and calloused. I interpreted it as saying veterans are disposable and they don’t matter.

In another tweet linking to the same op-ed, Tahir said, “Just about selling product and now using Vietnam vets to do it? You guys are just the pits.”

I cried when I read that one.

Tahir was referring to my Op-Ed about Bob and his friends, a group of amazing men who welcomed me into their lives and allowed me to help them quit smoking.

In Tahir’s eyes, I’m just another industry shill who was out to make a buck by keeping people addicted to nicotine. To him, my heart is as dark as the tar left in the lungs of those who smoke cigarettes.

The first time Bob came into my shop, he had $20 to spend. I sold him a $30 device, a $7 box of pods, and a $10 bottle of e-liquid for $20 (including sales tax). It never crossed my mind to use him. He was desperate to quit smoking, and I had the ability to help him.

The nine veterans Bob brought in over the next two weeks got the same deal. Some of them eventually wanted to quit all nicotine, and I helped them achieve that goal. It has never been about the money to me. It was about saving lives.

I shouldn't have cried when Tahir made that comment. I know, and anyone who knows me knows it isn’t true. But damn, it hurt. I felt like my integrity had been attacked. I tend to get defensive and angry when feeling attacked.

Tahir is very focused on preventing youth initiation of nicotine-containing products. He gives me the impression that it’s his mission in life to prevent that. It is a worthy goal.

He speaks often of addiction, and I visualize his interpretation of addiction to nicotine to be as “bad” as addiction to more potent substances. He refers to us needing our “fix” and pictures those of us who smoked and now vape as living a life of misery due to our nicotine addiction. I often feel his words stigmatize those who use nicotine.

While I agree that young people shouldn’t do adult things, I am very focused on helping people stop smoking. I specialize in the populations that have the most significant number of people who smoke and also have the most challenging time quitting smoking.

I visualize the “endgame” as a world where less than five percent of the world's population smokes commercial tobacco. Tahir’s vision of the “endgame” is a nicotine-free society.

While Tahir and I are not 100 percent in agreement on what the “endgame” is, there is overlap in what we believe and what we advocate for. We are both knowledgeable, vocal, and active.

I am often taken aback by his hatred of industry and his distaste for people's “addiction.” Sometimes, when he comments on one of my Op-Eds, his comments don’t make sense to me. It feels like he hasn’t read what I wrote or doesn’t understand the point I was trying to make.

In June, I finally decided to be curious and asked if he had read what I had written that Filter had published. That was the day I learned he considered things published there as tied to industry and nothing more than worthless propaganda. He wasn’t reading my Op-Eds. Nothing made him curious enough to motivate him to work past his hatred of industry.

The Op-Ed opened with some personal and painful information: “When I was 22, I watched my grandpa wheeled out of his home in a body bag. Aged 53, I sat in the dark with my mom as she breathed her last breath. My family tree is filled with people who died too soon from cancer, heart disease and other ailments linked to combustible tobacco use.”

Giving in to the insult I felt over him commenting on my work without reading it and wanting him to feel my pain, I replied: “The grandpa removed from his home in a body bag in that article was mine.”

I get really frustrated that some people in public health have no idea what those of us with lived experience have gone through and don’t listen to us. I had already made up my mind that Tahir was one of those people who didn’t have a clue what it was like to smoke or care about someone who does.

In that context, you can imagine how humbling it was to learn from Tahir that he, too, knows all about the pain that smoking causes families.

He replied to my tweet about my grandpa with a snapshot of his story, a story I am guilty of never asking to hear. “My dad also died from emphysema caused by his smoking,” is what Tahir shared with me.

Suddenly, it was clear to me why he hated the industry so much, why “addiction” to nicotine was so threatening, why he wanted to stop the world from ever starting the use of nicotine, and why he was concerned about a gateway to smoking. To him, initiating the use of nicotine leads to dire outcomes.

That is why publications that say anything terrible about vaping are believable to him. It reinforces those beliefs.

How is that different from why every publication that says anything good about vaping is believable to me?

While I see vaping as a way to break free from smoking, Tahir sees it as a way to perpetuate an addiction. I’m getting the sense that, to him, remaining addicted to nicotine is, in its own way, as harmful as smoking.

We have more common ground than either of us would have believed possible. Losing loved ones to smoking is the most binding of what we have in common. We are both working hard to spare others of that pain. And while I don’t recall either of us expressing our primary goal that way, as I look back on our many words, that is the underlying message we've given.

While writing this, I went back and read some of his tweets that were directed toward things I've tweeted. I had him muted for a long time, so many of the ones I read today are the first time I’ve seen them. To my surprise, he, too, found an instance where we were on common ground and agreed on something.

I am sitting here with cheeks glowing bright red as I blush in embarrassment for having said in the past that Tahir is always unreasonable and will never agree with anything we say!

That leaves me wondering, what else have I been wrong about?

Sometimes, it feels like people like Tahir hate me and everything I stand for. It is easy to take their words to heart and very tempting to strike back and shower them with my own venomous words.

The bone-chilling truth is that neither Tahir nor I will accomplish our goal of ending needless deaths and suffering due to smoking with a volley of hate-filled words on X (“Twitter”).

Doing so is using the other as a scapegoat for our pain, fear, and anger. The problem is, neither of us will end up feeling any better. We will only be more frustrated because we didn't get the other to agree with what we were saying.

In one of his sermons, Dr. King said: “Hate is just as injurious to the person who hates. Like an unchecked cancer, hate corrodes the personality and eats away its vital unity. Hate destroys a man’s sense of values and his objectivity. It causes him to describe the beautiful as ugly and the ugly as beautiful, and to confuse the true with the false and the false with the true.”

Many times, I have vocalized my displeasure to others about Tahir’s words. I am guilty of not inviting him to have a conversation. I wish we didn't live on opposite sides of the world. It would be enlightening to go out to dinner and hear his story and to share mine. It would be good to share our mutual pain in the losses we’ve suffered and our dreams of helping make the world a better place.

I can not make Tahir read what I’ve written in the Op-Eds he comments on, and I can't force him to have a civil conversation with me. I have no control over how he feels about me, how he talks to me, or how disgusted he feels toward me. I am powerless over all those things.

What I do have power over is how I react to his words. I can let them hurt me and make me angry. I can let those feelings fester and grow until I feel hate towards him. I can let that hate turn into a cancer that eats my beautiful soul and breaks my kind heart. I can waste my time and lash out with unkind words.

What would that prove? That I’m capable of being mean and disrespectful? That’s not the legacy I want to be known for!

I want to either not take the bait and avoid responding to the stigmatizing and disrespectful comments, or if I respond, keep personalities and feelings out of it and reply with facts.

While I may never influence Tahir, the whole world can see my words. My knowledge and love for others might cause someone who hasn’t been able to quit smoking to give an alternative product a try.

At the end of the day, that person who smokes is all that matters.

I keep thinking that when the words of people like Tahir upset me, I need thicker skin, but that thinking might have been wrong. Perhaps I need a more compassionate heart.

It just might be that his words aren’t about me. They might be about how strongly he feels based on his lived experiences. Maybe instead of taking his words to heart, I should let his concerns into my heart.

There will be those who will tell me I’m wrong. They will say that, at times, Tahir makes them feel disliked, disrespected, and unheard. They will say that Tahir dismisses them and accuses them of things that aren’t true. Because of this, he doesn’t deserve compassion or to be sheltered from personal attacks.

At times like this, my grandpa's voice is loud and clear in my head. He often told me that what other people do or say reflects on them, not me. My actions and words reflect on me. If I want to change something, I should lead by example, and being a good leader means doing the right thing.

Grampa often marveled how my few drops of “Irish blood” could get the better of me. There were times I could be a hothead. Sometimes, he’d shake his head, get on the tractor, and drive away, leaving me well aware I had once again crossed a line.

He said I had a gift and a curse all in one. I never needed to raise a fist to make someone cry. I could do that purely with words. Awful, ugly, hurtful words.

But I could also use my words to make people think and feel—feelings so strong that their eyes would fill with tears. Grandpa encouraged me to focus on the gift part.

By then, I was a teenager, and I didn’t pay the attention I should have to his advice, but I’ve never forgotten what he told me.

Gramps always treated people with kindness and respect, no matter how they treated him. Whatever the circumstance, he took the high road. It has taken me many years to figure out how important this is. I am proud to finally walk in the footsteps he laid down for me when I was a child.

Years ago, my strategy was to fight fire with fire. That didn’t work for me.

My calling is to fight hate and fear with love. I am finally where I belong.

~ Skip “Be Kind” Murray